The foundation for the British Empire was laid when England and Scotland were separate kingdoms. In 1496 King Henry VII of England, following the successes of Portugal and Spain in overseas exploration, commissioned John Cabot to lead a voyage to discover a route to Asia via the North Atlantic.[4] Cabot sailed in 1497, and though he successfully made landfall on the coast of Newfoundland (mistakenly believing, like Christopher Columbus five years earlier, that he had reached Asia),[5] there was no attempt to found a colony. Cabot led another voyage to the Americas the following year but nothing was heard from his ships again.[6]

No further attempts to establish English colonies in the Americas were made until well into the reign of Elizabeth I, during the last decades of the 16th century.[7] The Protestant Reformation had made enemies of England and Catholic Spain.[4] In 1562, the English Crown sanctioned the privateers John Hawkins and Francis Drake to engage in slave-raiding attacks against African towns and Portuguese ships off the coast of West Africa[8] with the aim of breaking into the Atlantic trade system. This effort was rebuffed and later, as the Anglo-Spanish Wars intensified, Elizabeth lent her blessing to further piratical raids against Spanish ports in the Americas and shipping that was returning across the Atlantic, laden with treasure from the New World.[9] At the same time, influential writers such as Richard Hakluyt and John Dee (who was the first to use the term "British Empire")[10] were beginning to press for the establishment of England's own empire, to rival those of Spain and Portugal. By this time, Spain was firmly entrenched in the Americas, Portugal had established a string of trading posts and forts from the coasts of Africa and Brazil to China, and France had begun to settle the Saint Lawrence River, later to become New France.

Plantations of Ireland

Though a relative late comer in comparison to Spain and Portugal, England had been engaged in colonial settlement in Ireland, drawing on precedents dating back to the Norman invasion in 1171.[11][12] The 16th century Plantations of Ireland, run by English colonists, were a precursor to the colonies established on the North Atlantic seaboard,[13] and several people involved in these projects also had a hand in the early colonisation of North America, particularly a group known as the "West Country men", which included Humphrey Gilbert, Walter Raleigh, Francis Drake, John Hawkins, Richard Grenville and Ralph Lane.[14]

"First British Empire" (1583–1783)

In 1578, Queen Elizabeth I granted a patent to Humphrey Gilbert for discovery and overseas exploration.[15] That year, Gilbert sailed for the West Indies with the intention of engaging in piracy and establishing a colony in North America, but the expedition was aborted before it had crossed the Atlantic.[15][16] In 1583 he embarked on a second attempt, on this occasion to the island of Newfoundland whose harbour he formally claimed for England, though no settlers were left behind. Gilbert did not survive the return journey to England, and was succeeded by his half-brother, Walter Raleigh, who was granted his own patent by Elizabeth in 1584. Later that year, Raleigh founded the colony of Roanoke on the coast of present-day North Carolina, but lack of supplies caused the colony to fail.[17]

In 1603, King James VI of Scotland ascended to the English throne and in 1604 negotiated the Treaty of London, ending hostilities with Spain. Now at peace with its main rival, English attention shifted from preying on other nations' colonial infrastructure to the business of establishing its own overseas colonies.[18] The British Empire began to take shape during the early 17th century, with the English settlement of North America and the smaller islands of the Caribbean, and the establishment of a private company, the English East India Company, to trade with Asia. This period, until the loss of the Thirteen Colonies after the American War of Independence towards the end of the 18th century, has subsequently been referred to as the "First British Empire".[19]

Americas, Africa and the slave trade

The Caribbean initially provided England's most important and lucrative colonies,[20] but not before several attempts at colonisation failed. An attempt to establish a colony in Guiana in 1604 lasted only two years, and failed in its main objective to find gold deposits.[21] Colonies in St Lucia (1605) and Grenada (1609) also rapidly folded, but settlements were successfully established in St. Kitts (1624), Barbados (1627) and Nevis (1628).[22] The colonies soon adopted the system of sugar plantations successfully used by the Portuguese in Brazil, which depended on slave labour, and—at first—Dutch ships, to sell the slaves and buy the sugar. To ensure that the increasingly healthy profits of this trade remained in English hands, Parliament decreed in 1651 that only English ships would be able to ply their trade in English colonies. This led to hostilities with the United Dutch Provinces—a series of Anglo-Dutch Wars—which would eventually strengthen England's position in the Americas at the expense of the Dutch. In 1655 England annexed the island of Jamaica from the Spanish, and in 1666 succeeded in colonising the Bahamas.

England's first permanent settlement in the Americas was founded in 1607 in Jamestown, led by Captain John Smith and managed by the Virginia Company, an offshoot of which established a colony on Bermuda, which had been discovered in 1609. The Company's charter was revoked in 1624 and direct control was assumed by the crown, thereby founding the Colony of Virginia.[23] The Newfoundland Company was created in 1610 with the aim of creating a permanent settlement on Newfoundland, but was largely unsuccessful. In 1620, Plymouth was founded as a haven for puritan religious separatists, later known as the Pilgrims.[24] Fleeing from religious persecution would become the motive of many English would-be colonists to risk the arduous trans-Atlantic voyage: Maryland was founded as a haven for Roman Catholics (1634), Rhode Island (1636) as a colony tolerant of all religions and Connecticut (1639) for Congregationalists. The Province of Carolina was founded in 1663. In 1664, England gained control of the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam (renamed New York) via negotiations following the Second Anglo-Dutch War, in exchange for Suriname. In 1681, the colony of Pennsylvania was founded by William Penn. The American colonies were less financially successful than those of the Caribbean, but had large areas of good agricultural land and attracted far larger numbers of English emigrants who preferred their temperate climates.[25]

In 1670, King Charles II granted a charter to the Hudson's Bay Company, granting it a monopoly on the fur trade in what was then known as Rupert's Land, a vast stretch of territory that would later make up a large proportion of Canada. Forts and trading posts established by the Company were frequently the subject of attacks by the French, who had established their own fur trading colony in adjacent New France.[26]

Two years later, the Royal African Company was inaugurated, receiving from King Charles a monopoly of the trade to supply slaves to the British colonies of the Caribbean.[27] From the outset, slavery was the basis of the British Empire in the West Indies. Until the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, Britain was responsible for the transportation of 3.5 million African slaves to the Americas, a third of all slaves transported across the Atlantic.[28] To facilitate this trade, forts were established on the coast of West Africa, such as James Island, Accra and Bunce Island. In the British Caribbean, the percentage of the population of black people rose from 25 percent in 1650 to around 80 percent in 1780, and in the Thirteen Colonies from 10 percent to 40 percent over the same period (the majority in the southern colonies).[29] For the slave traders, the trade was extremely profitable, and became a major economic mainstay for such western British cities as Bristol and Liverpool, which formed the third corner of the so-called triangular trade with Africa and the Americas. For the transportees, harsh and unhygienic conditions on the slaving ships and poor diets meant that the average mortality rate during the middle passage was one in seven.[30]

In 1695, the Scottish parliament granted a charter to the Company of Scotland, which proceeded in 1698 to establish a settlement on the isthmus of Panama, with a view to building a canal there. Besieged by neighbouring Spanish colonists of New Granada, and afflicted by malaria, the colony was abandoned two years later. The Darien scheme was a financial disaster for Scotland—a quarter of Scottish capital[31] was lost in the enterprise—and ended Scottish hopes of establishing its own overseas empire. The episode also had major political consequences, persuading the governments of both England and Scotland of the merits of a union of countries, rather than just crowns.[32] This was achieved in 1707 with the Treaty of Union, establishing the Kingdom of Great Britain.

Rivalry with the Netherlands in Asia

At the end of the 16th century, England and the Netherlands began to challenge Portugal's monopoly of trade with Asia, forming private joint-stock companies to finance the voyages—the English, later British, and Dutch East India Companies, chartered in 1600 and 1602 respectively. The primary aim of these companies was to tap into the lucrative spice trade, and they focused their efforts on the source, the Indonesian archipelago, and an important hub in the trade network, India. The close proximity of London and Amsterdam across the North Sea and intense rivalry between England and the Netherlands inevitably led to conflict between the two companies, with the Dutch gaining the upper hand in the Moluccas (previously a Portuguese stronghold) after the withdrawal of the English in 1622, and the English enjoying more success in India, at Surat, after the establishment of a factory in 1613.

Although England would ultimately eclipse the Netherlands as a colonial power, in the short term the Netherlands' more advanced financial system[33] and the three Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th century left it with a stronger position in Asia. Hostilities ceased after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 when the Dutch William of Orange ascended the English throne, bringing peace between the Netherlands and England. A deal between the two nations left the spice trade of the Indonesian archipelago to the Netherlands and the textiles industry of India to England, but textiles soon overtook spices in terms of profitability, and by 1720, in terms of sales, the English company had overtaken the Dutch.[33] The English East India Company shifted its focus from Surat—a hub of the spice trade network—to Fort St George (later to become Madras), Bombay (ceded by the Portuguese to Charles II of England in 1661 as dowry for Catherine de Braganza) and Sutanuti (which would merge with two other villages to form Calcutta).

Global struggles with France

Peace between England and the Netherlands in 1688 meant that the two countries entered the Nine Years' War as allies, but the conflict—waged in Europe and overseas between France, Spain and the Anglo-Dutch alliance—left the English a stronger colonial power than the Dutch, who were forced to devote a larger proportion of their military budget on the costly land war in Europe.[34] The 18th century would see England (after 1707, Britain) rise to be the world's dominant colonial power, and France becoming its main rival on the imperial stage.[35]

The death of Charles II of Spain in 1700 and his bequeathal of Spain and its colonial empire to Philippe of Anjou, a grandson of the King of France, raised the prospect of the unification of France, Spain and their respective colonies, an unacceptable state of affairs for England and the other powers of Europe.[36] In 1701, Britain, Portugal and the Netherlands sided with the Holy Roman Empire against Spain and France in the War of the Spanish Succession, which lasted until 1714. At the concluding Treaty of Utrecht, Philip renounced his and his descendants' right to the French throne and Spain lost its empire in Europe.[37] The British Empire was territorially enlarged: from France, Britain gained Newfoundland and Acadia, and from Spain, Gibraltar and Minorca. Gibraltar, which is still a British territory to this day, became a critical naval base and allowed Britain to control the Atlantic entry and exit point to the Mediterranean. Minorca was returned to Spain at the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, after changing hands twice. Spain also ceded the rights to the lucrative asiento (permission to sell slaves in Spanish America) to Britain.[38]

The Seven Years' War, which began in 1756, was the first war waged on a global scale, fought in Europe, India, North America, the Caribbean, the Philippines and coastal Africa. The signing of the Treaty of Paris (1763) had important consequences for the future of the British Empire. In North America, France's future as a colonial power there was effectively ended with the recognition of British claims to Rupert's Land,[26] the ceding of New France to Britain (leaving a sizeable French-speaking population under British control) and Louisiana to Spain. Spain ceded Florida to Britain. In India, the Carnatic War had left France still in control of its enclaves but with military restrictions and an obligation to support British client states, effectively leaving the future of India to Britain. The British victory over France in the Seven Years' War therefore left Britain as the world's dominant colonial power.[39]

Rise of the "Second British Empire" (1783–1815)

Company rule in India

During its first century of operation, the English East India Company focused on trade with the Indian subcontinent, as it was not in a position to challenge the powerful Mughal Empire,[40] which had granted it trading rights in 1617. This changed in the 18th century as the Mughals declined in power and the East India Company struggled with its French counterpart, the Compagnie française des Indes orientales, during the Carnatic Wars in the 1740s and 1750s. The Battle of Plassey in 1757, which saw the British, led by Robert Clive, defeat the French and their Indian allies, left the Company in control of Bengal and as the major military and political power in India.[24] In the following decades it gradually increased the size of the territories under its control, either ruling directly or via local puppet rulers under the threat of force from the British Indian Army, the vast majority of which was composed of native Indian sepoys.[41] The Company's conquest of India was complete by 1857. The Indian Rebellion that year eventually led to the end of the East India Company and India came to be ruled directly by the British Raj.

Loss of the Thirteen American Colonies

During the 1760s and 1770s, relations between the Thirteen Colonies and Britain became increasingly strained, primarily because of resentment of the British Parliament's attempts to govern and tax American colonists without their consent,[42] summarised at the time by the slogan "No taxation without representation". Disagreement over the American colonists' guaranteed Rights as Englishmen turned to violence and, in 1775, the American War of Independence began. The following year, the colonists declared the independence of the United States and, with assistance from France, Spain, and the Netherlands would go on to win the war in 1783.

The loss of such a large portion of British America, at the time Britain's most populous overseas possession, is seen by historians as the event defining the transition between the "first" and "second" empires,[43] in which Britain shifted its attention away from the Americas to Asia, the Pacific and later Africa. Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, had argued that colonies were redundant, and that free trade should replace the old mercantilist policies that had characterised the first period of colonial expansion, dating back to the protectionism of Spain and Portugal.[39][44] The growth of trade between the newly independent United States and Britain after 1783 seemed to confirm Smith's view that political control was not necessary for economic success.[45][46] Tensions between the two nations escalated during the Napoleonic Wars, as Britain tried to cut off American trade with France, and boarded American ships to impress into the Royal Navy men of British birth. The U.S. declared war, the War of 1812, in which both sides tried to make major gains at the other's expense. Both failed and the Treaty of Ghent, ratified in 1815, kept the pre-war boundaries.[47]

Events in America influenced British policy in Canada, where between 40,000 and 100,000[48] defeated Loyalists had migrated from America following independence. The 14,000 Loyalists who went to the Saint John River in Nova Scotia felt too far removed from the provincial government in Halifax, so London split off New Brunswick as a separate colony in 1784.[49] The Constitutional Act of 1791 created the provinces of Upper Canada (mainly English-speaking) and Lower Canada (mainly French-speaking) to defuse tensions between the French and British communities, and implemented governmental systems similar to those employed in Britain, with the intention of asserting imperial authority and not allowing the sort of popular control of government that was perceived to have led to the American Revolution.[50]

Exploration of the Pacific

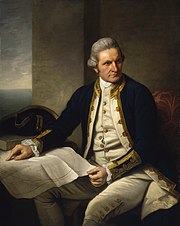

Since 1718, transportation to the American colonies had been a penalty for various criminal offences in Britain, with approximately one thousand convicts transported per year across the Atlantic.[51] Forced to find an alternative location after the loss of the Thirteen Colonies in 1783, the British government turned to the newly discovered lands of Australia.[52] The western coast of Australia had been discovered for Europeans by the Dutch explorer Willem Jansz in 1606 and was later named by the Dutch East India Company New Holland,[53] but there was no attempt to colonise it. In 1770 James Cook discovered the eastern coast of Australia while on a scientific voyage to the South Pacific Ocean, claimed the continent for Britain, and named it New South Wales.[52] In 1778, Joseph Banks, Cook's botanist on the voyage, presented evidence to the government on the suitability of Botany Bay for the establishment of a penal settlement, and in 1787 the first shipment of convicts set sail, arriving in 1788.[52] Britain continued to transport convicts to New South Wales until 1840, at which time the colony's population numbered 56,000, the majority of whom were convicts, ex-convicts or their descendants.[54] The Australian colonies became profitable exporters of wool and gold.[54]

During his voyage, Cook also visited New Zealand, first discovered by Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1642, and claimed the North and South islands for the British crown in 1769 and 1770 respectively. Initially, interaction between the native Maori population and Europeans was limited to the trading of goods. European settlement increased through the early decades of the 19th century, with numerous trading stations established, especially in the North. In 1839, the New Zealand Company announced plans to buy large tracts of land and establish colonies in New Zealand. On 6 February 1840, Captain William Hobson and around 40 Maori chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi.[55] This treaty is considered by many to be New Zealand's founding document,[56] but differing interpretations of the Maori and English versions of the text[57] have meant that it continues to be a source of dispute.[58]

War with Napoleonic France

Britain was challenged again by France under Napoleon, in a struggle that, unlike previous wars, represented a contest of ideologies between the two nations.[59] It was not only Britain's position on the world stage that was threatened: Napoleon threatened to invade Britain itself, just as his armies had overrun many countries of continental Europe.

The Napoleonic Wars were therefore ones in which Britain invested large amounts of capital and resources to win. French ports were blockaded by the Royal Navy, which won a decisive victory over a Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar in 1805. Overseas colonies were attacked and occupied, including those of the Netherlands, which was annexed by Napoleon in 1810. France was finally defeated by a coalition of European armies in 1815. Britain was again the beneficiary of peace treaties: France ceded the Ionian Islands, Malta (which it had occupied in 1797 and 1798 respectively), Seychelles, Mauritius, St Lucia, and Tobago; Spain ceded Trinidad; the Netherlands Guyana, and the Cape Colony. Britain returned Guadeloupe, Martinique, Goree, French Guiana, and Réunion to France, and Java, and Suriname to the Netherlands.

Abolition of slavery

Under increasing pressure from the abolitionist movement, Britain enacted the Slave Trade Act in 1807 which abolished the slave trade in the Empire. In 1808, Sierra Leone was designated an official British colony for freed slaves.[61] The Slavery Abolition Act passed in 1833 made not just the slave trade but slavery itself illegal, emancipating all slaves in the British Empire on 1 August 1834.

No comments:

Post a Comment